Children of prisoners: The story India’s prison data doesn’t tell

Across the country, children of incarcerated women, and men, (parents) remain among the most invisible groups in public policy; some spend their early years inside prisons with their mothers

Recently, the Karnataka state child rights panel raised concerns about the welfare of children of prison inmates. It drew attention to a long-ignored truth: India’s prison quietly punishes children – and bears lifelong consequences of parental incarceration.

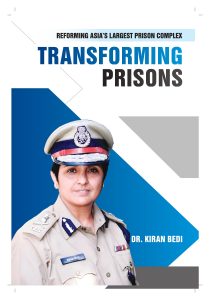

I recall my first day inside Tihar jail as IG prisons. The first ward I visited was the one lodging women. As I entered, I saw a swarm of children. I was shocked. I asked the superintendent what they were doing here. He told me they are here with their mothers. The Indian prison system allows mothers to bring in their children to stay with them up to the age of six. They share the same barracks.

I asked: “What about their schooling?” He said we have no provision. He further told me that the only outing they have is when they accompany their mother to the trial courts. I saw some children with swollen heads. I asked if a doctor or a child specialist visits them? He said. No. I asked do they have health cards? He said no. I was aghast. This was 1993. What we did immediately thereafter is history which is documented in my book ‘It’s Always Possible’.

Across the country, children of incarcerated women, and men, (parents) remain among the most invisible groups in public policy. Some spend their early years inside prisons with their mothers. Thousands more are left outside, abruptly separated from parental care, often without structured support. In either case, they experience disruption, stigma, educational setbacks, and emotional trauma that can follow them into adulthood. These are not side effects of incarceration; they are systemic deficiencies.

Recent debates on prison reforms have begun to acknowledge a deeper problem: numbers alone do not tell the full story. For children of prisoners, the problem is even starker. Their story is not just inadequately told, it is not counted at all. This absence of data has real consequences. Without formal identification, children affected by incarceration fall outside the purview of child protection systems. There is no uniform national mechanism to record whether a prisoner has dependent children, where those children are, or who is responsible for their care. Invisibility becomes neglect, and neglect becomes vulnerability.

What emerges here is the need to recognise ‘social parenting’ as a public responsibility. When incarceration disrupts biological parenting, the state and society acquires a temporary parental obligation. This is not an act of benevolence, it flows from constitutional guarantees of dignity, equality, and special protection for children. No child should be penalised – socially or developmentally – for the actions of a parent. Judicial interventions by high courts have occasionally acknowledged this responsibility. However, prisons fall under the state list, and piecemeal judicial directions lead to uneven outcomes. A child’s access to care cannot depend on which state a prison is located in. A uniform national approach, ideally guided by directions from the Supreme Court, is essential to ensure that children of incarcerated parents are identified, protected, and supported across the country.

A crucial starting point is data reform. Every prison in India should be mandated to record information about children affected by incarceration – both those residing inside prisons with mothers and those left outside when a parent is jailed. This information must be integrated into prison management software and linked automatically to district child protection units and state child rights commissions. Accountability cannot exist without visibility, and visibility begins with data that captures human consequences, not just headcounts.

Prison reforms discourse increasingly recognises that prisons function not merely as detention spaces but as social ecosystems. Meaningful correction requires social workers, counsellors, educators, and mental health professionals who act as bridges between prisoners, their families, and the state. Yet this bridge does not extend to prisoners’ children. They remain the missing link in India’s correctional framework.

This is where lived practice offers clarity. Since 1995, India Vision Foundation (IVF) has worked with minors in prisons across multiple states, particularly children accompanying incarcerated mothers. When these children reach the legally mandated age at which they can no longer remain inside prisons, the Foundation ensures their safe transition – prioritising education, healthcare, emotional well-being, and secure family placement. IVF’s work demonstrates what the system has long overlooked: The organisation’s guiding principle – save the next victim – captures a truth that prison statistics cannot. Prevention does not begin inside courtrooms or cell blocks; it begins with protecting children from being quietly absorbed into cycles of neglect and institutionalisation.

What IVF has achieved with limited resources can be scaled through institutional mechanisms. A national framework for children of prisoners would require coordinated action: prisons as points of identification, child protection systems as custodians of care, child rights commissions as oversight bodies, and civil society organisations as implementation partners. Educational institutions, residential schools where necessary, and extended families must all be part of this ecosystem of care.

The Karnataka panel’s intervention should not remain an isolated moment. It should mark the beginning of a national reckoning – one that recognises children of prisoners not as collateral damage, but as citizens deserving protection, opportunity, and hope.

kiranbediofficial@gmail.com

(The writer, India’s first female IPS officer, is former lieutenant governor of Puducherry)